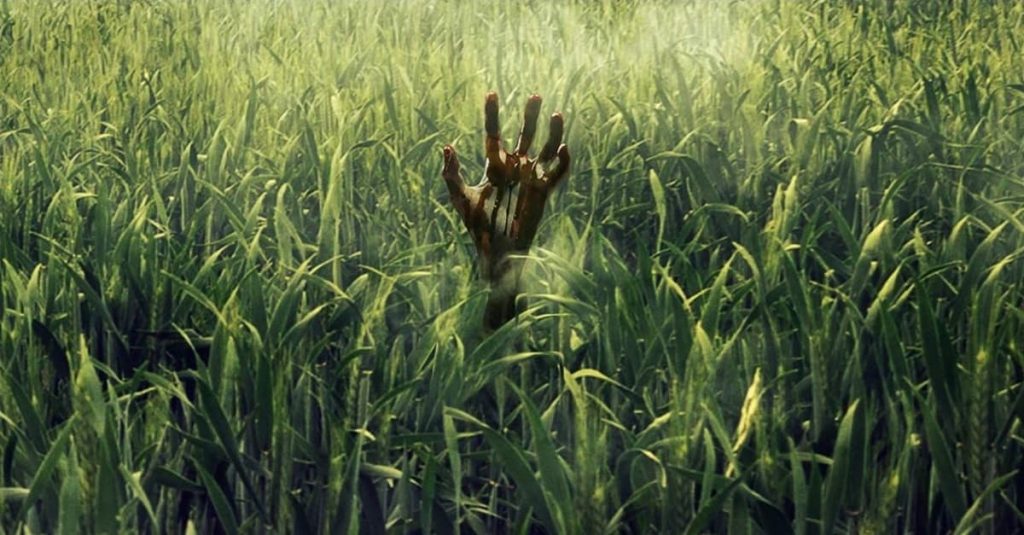

The premise for this movie (based on a novella by Stephen King and his son Joe Hill) is so exciting—we enter the grass very quickly, with only about ten minutes of establishing our main characters, siblings Becky and Cal. Hearing a child cry for help from within a vast field is such a good hook, especially when the second voice chimes in, screaming at the child to stop calling people into the grass, don’t come into the grass. It’s so creepy and foreboding, and I liked how Becky displayed an almost unconscious wariness of the grass; while her brother is about to jovially stroll in, confident he can help, she hangs back and her hand drifts towards her stomach (she’s six months pregnant), staring at the innocuous-looking grass and obviously feeling uncomfortable. Of course, both she and Cal go into the grass, because we were promised a movie.

I love the initial elements present in In the Tall Grass; how the grass separates them immediately; how sounds in the grass are always moving (Cal hears Becky from ahead of him, but then when she calls next, suddenly her voice is behind him, and much fainter). The claustrophobic nature of the grass itself is an excellent mood-setter, a seemingly banal jungle that becomes more and more sinister as the film progresses. It’s an easily understandable, effectively scary premise, and I was excited to watch the characters figure out The Rules (for there are always Rules, and to defeat the horror you must figure out The Rules). I was excited by all the potential ItTG was offering me. Then—all the other shit came in.

The problems plaguing ItTG can be summed up in two words: logical consistency. ItTG plays with so many concepts—some of them interesting, some weird, and some unpleasant—but it refuses to find a middle ground where its ideas are consistent (tonally and plot-wise) enough to make sense, but also clever enough that it’s not immediately obvious what’s going on. Some mysterious aspects of the grass are explained and de-mystified to the point of becoming boring, while other aspects are only paid lip service to. Instead of utilizing Rules to escape the grass, the characters leap to bizarre conclusions that somehow work, as the film’s logic bends to allow whatever it wants. It’s similar to a phenomenon I find very irritating in detective novels, where near the end of the book the detective identifies the culprit based on crucial information that the reader was never privy to. Look, a mystery novel technically doesn’t have to be written so the reader can solve it, but it’s a hell of a lot more fun if it is. The logic of the ancient rock and death in the grass doesn’t have to work consistently, but it’ll be way more satisfying to see our heroes defy the grass through a loophole or clever solution if it does.

To be completely honest, the main reason I found myself disliking In the Tall Grass so much basically came down to one scene, late in the movie. (This will serve as a spoiler and a content warning; skip to the next paragraph if you don’t want or need either of those.) Becky is six months pregnant at the start of the movie, and there’s an odd subplot involving her unborn baby and the big ancient rock that seemingly controls the grass; she keeps having visions involving her baby, blood, the rock, and the grass. These are unnerving, but for the most part don’t really amount to anything, except for the most upsetting scene in the movie: in the third act, Becky starts going through labor, and delivers her baby in the mud and the grass while a huge thunderstorm crashes above, the ancient rock looming and seemingly observing. It’s very tense, and adds an urgency to Becky and Cal’s quest to get out of the grass. Becky passes out from the strain, and when she wakes up, it’s to her brother Cal (who has touched the rock and thus been infected with its madness) feeding her bites of food. Exhausted and hungry, she eats what he gives her, while the viewer experiences mounting feelings of dread. Eventually, she asks what she’s eating, starting to panic, and Cal laughs and says it’s only grass—the leaves, the stems, the seeds. Becky asks to hold her baby. Cal says she can’t right now. From the little glimpses we see, it’s obvious he isn’t feeding her grass, and the viewer’s dreadful fear is confirmed. Now, this is not some sacred ground no director or writer has ever dared to touch; Snowpiercer and The Road both feature a scene of this sort. Except in those films, it’s an example of humanity at its lowest, committing one of the most taboo acts in order to survive, and there’s some exploration of the psychological toll this takes on the characters. This is not present in In the Tall Grass; it feels like more of a shocking scare for the sake of a scare, and I was surprised at how much this scene repulsed me. Everybody’s mileage will vary, obviously, and for me I think this useless, grotesque scene reminded me of the kind of horror I hate; the needlessly exploitative, the kind without style or substance—the laziest type of horror that isn’t used to explore any themes or relieve a cultural worry, but just exists because it will get a reaction.

(The spoilers end here.) But as I intimated, brutal horror is not inherently bad or worthless. One of my favorite Stephen King books is The Long Walk, one of several he published under a pseudonym—Richard Bachman—in the 1980s. King’s writing as Bachman tended to be darker; a little angrier and a little more cynical, which usually isn’t my style; but there was something about the brutality of these books that I was drawn to. In The Long Walk, set in a vaguely dystopian future, 100 boys sign up for the Long Walk every year, an event where the boys—walk. The last one standing gets an “unimaginable prize” (we can infer it’s insane amounts of money). As you could maybe assume, the entire book is just the boys walking, getting to know each other, their number getting smaller and smaller as the exertion starts taking its toll on the other walkers. It’s like if Waiting for Godot was made into an exploitation film, and I really, really love it. The difference between my love of the brutal horror in The Long Walk versus In the Tall Grass relates to a very common problem King has in his writing, which is this: reading The Long Walk I, ironically, felt like King invited me for a walk (hey here’s a cool premise, wanna hear about it?), and we’re leisurely strolling along, making steady progress along an interesting route, knowing that when we stop and rest it will be very satisfying, a reward for the effort we put in. When watching In the Tall Grass, there is the same invitation (hey look at this trailer, pretty neat huh?), but then Stephen King kidnaps me, straps me into a rollercoaster, and as the coaster rides up, down, and along the crazy rails, he monologues his extensive and complex manifesto at me, while I sit there, confused, angry, and not a little sick.

When I reflect on The Long Walk, I think about the worth and expendability of human life, of that unpleasant but irresistible desire to look closely at that car wreck, that crime scene, that dead body. When I reflect on In the Tall Grass, I think about some very cool ideas that, instead of showing me a new perspective or inspiring new avenues of thought, just left me uncomfortable and unhappy.